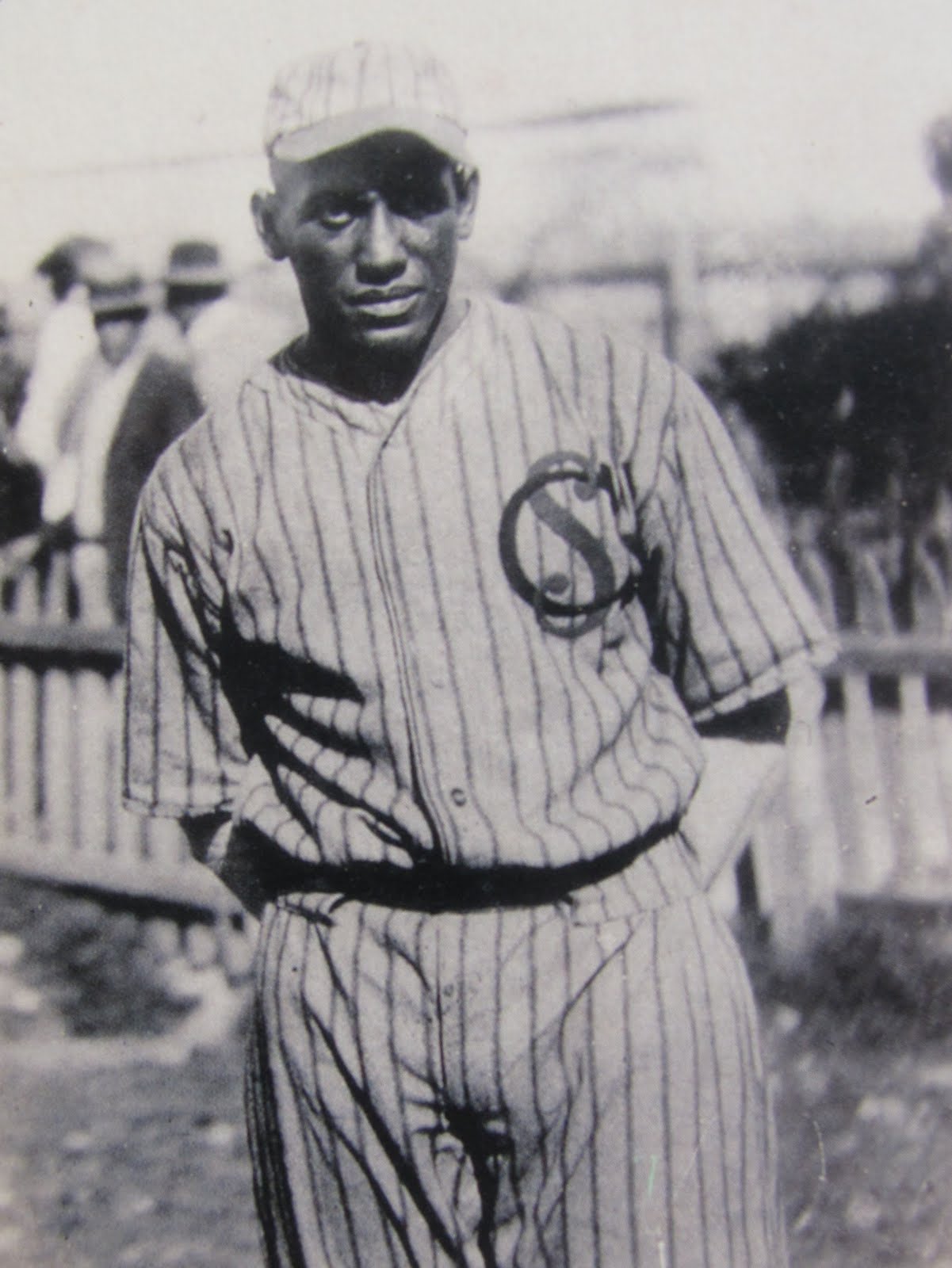

THE TALENT AND THE TEMPER OF OLIVER MARCELLE

Long before Jackie Robinson integrated the Major Leagues in 1947, sportswriters in African-American newspapers had been advocating for the big leagues to allow black athletes onto the field. One example appears in the Sept. 1, 1934 Colored Baseball & Sports Monthly, written by editor Nat Trammell, a document recently digitized by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

In “Will Colored Players enter the Major Leagues?”, Trammell points out that blacks and whites have already played with and against each other, and he references a number of exhibition games, specific players, and the Cuban winter leagues. It was in Cuba, he recounts, where Bill Holland, an ace pitcher for the Black Yankees, facing black, white, and Latino players, won $500 in gold for being the best pitcher in the league (over $6,800 in 2016 dollars). Then, almost as an afterthought, Trammell adds, “Marcel, leading colored third baseman, took the hitting honors away.”

Trammell may have given brief notice to Oliver Marcelle (sometimes spelled “Marcell,” “Marcel” or “Marsel”) because he was probably not who Trammell wanted to see integrate the Major Leagues; he was known as a terrific player, but equally for having a terrific temper.

But Marcelle, a Creole from Louisiana, is no footnote in Negro League history. And that season in Cuba, when Holland and Marcelle each carried home $500 worth of gold, they were teammates on a historic team. Even today, Cubans speak of the 1924 Leopardos de Santa Clara like many baseball fans speak of the 1927 Yankees. It was simply the greatest team the country had ever known.

Besides Marcelle and Holland, Santa Clara had Oscar Charleston and Cuban pitcher José Méndez, both later elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. And while the other three teams in the league were comprised of big league players and future Hall of Famers like Martín Dihigo and John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, they offered little competition to the Leopardos.

So dominant were the Leopardos – frequently scoring in the double-digits – that they took an insurmountable lead in the standings. With the championship a foregone conclusion, attendance dropped. The league responded by simply cutting the season short and declaring Santa Clara the champions. They finished with a 36-11 record (.766 winning percentage), 11.5 games in front of the next best team. The league then broke up the last-place team and reassigned its best players to the other two teams competing against Santa Clara, for a shortened second season, which Santa Clara won as well (though only by half a game). Santa Clara led the league in virtually every offensive category, including runs, doubles, home runs, hits, and stolen bases. The team hit a collective .331, a Cuban League record, with Marcelle leading the way at .393.

Marcelle would continue to recruit black players to the Denver Post Tournament, and continue to paint houses. He died in 1949, just before his 54th birthday, of arteriosclerosis, in poverty, and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Larry Brunt is the Museum’s digital strategy intern in the Class of 2016 Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development. To support the Hall of Fame Digital Archive Project, please visitwww.baseballhall.org/DAP

Larry Brunt

0 comentarios